In scenes straight out of a Hollywood action film, last week former Liberian strongman Charles Taylor found himself in a dragnet when the Nigerian government, after years of protecting him, finally announced plans to turn the ex-dictator over to a UN special court to be tried for war crimes and atrocities committed in support of civil war in Sierra Leone. Within 24 hours Taylor had escaped, and rumor was that he might attempt a coup back in Liberia's capital. But the Nigerians nabbed him, and Taylor is now in UN custody in Freetown, Sierra Leone on his way to trial.

In scenes straight out of a Hollywood action film, last week former Liberian strongman Charles Taylor found himself in a dragnet when the Nigerian government, after years of protecting him, finally announced plans to turn the ex-dictator over to a UN special court to be tried for war crimes and atrocities committed in support of civil war in Sierra Leone. Within 24 hours Taylor had escaped, and rumor was that he might attempt a coup back in Liberia's capital. But the Nigerians nabbed him, and Taylor is now in UN custody in Freetown, Sierra Leone on his way to trial.

If things go as planned from now on, Taylor's extradition could become a major step toward justice and accountability in Africa. Though Chad, Ethiopia, Uganda and many other countries have suffered under brutal and reckless leaders, none of these criminal heads of state has ever been brought to trial. The U.S. played a constructive role in trying to break the pattern with Taylor, pushing hard on newly elected Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf to demand his extradition from Nigeria.

U.S. and UN pressure, coupled with Johnson-Sirleaf's call, forced Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo to depart from a longstanding but deeply destructive policy of unwavering comity among African leaders. Feeling sidelined and mistreated by the rest of the world, African leaders have sought strength in solidarity and been reluctant to break ranks regardless of how illegitimate, incompetent, or plain evil individual members of the fraternity are.

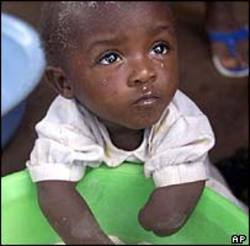

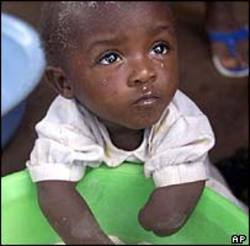

When Interpol first tried to arrest Taylor at a Summit of East African leaders in 2003, Obasanjo and others balked at the affront to a head of state representing his country at a multinational gathering. This despite Taylor's role in violating 8 peace accords and 13 ceasefires in his region, and his continued efforts to bedevil attempts to settle a conflict fought by hacking the limbs and gouging the eyes of children.

African leaders found it unseemly that Taylor would be tried as a sitting President by a "not well recognized court" and a "junior legal luminary" (the American prosecutor). So instead of being held accountable for his crimes, Taylor was granted asylum in Nigeria on condition that he stay out of Liberian affairs and that if a duly elected Liberian government were ever to ask, he would be handed over. The first condition was never enforced, and Taylor continued to have in-person contacts and financial dealings with Liberian rebels.

There are rumors that Obasanjo's fealty to Taylor continued even after the Nigerian President agreed to accede to the extradition last week. The speed with which Nigerian policy recaptured Taylor after his escape raises questions over whether the Nigerian government may have known his whereabouts all along.

But that aside, the reality of Taylor being put in the dock to account for his crimes before a hybrid international and Sierra Leonian court sends the following important messages:

1. That even a continent with no greater downfall than official corruption and abuse, there is hope for accountability. The road to Taylor's capture was sufficiently long and tortured that most wayward African despots will still be able to comfort themselves that they aren't important enough to the United States to ever attract the level of attention and pressure put on the Taylor case. But if well-publicized over the next year or two, Taylor's trial and fate could have some constraining effect.

2. That the firm fraternity of African leaders, thick enough to mask all manner of misdeeds, has its limits. There have been a few tentative signs in recent months that African leaders are starting to recognize the folly of protecting their own irrespective of the geopolitical and moral costs. They kept Sudan from assuming the rotating presidency of the African Union and now, though under duress, have turned in Taylor. If this trend can gain steam, competent and incorruptible African leaders could one day be the most powerful force the continent has for cracking down on those who are neither.

3. That the U.S., in spite of everything, can under the right circumstances still be a force for accountability and the rule of law. We've spent a lot of time at Democracy Arsenal and elsewhere talking about the violence that's been done to America's international legitimacy by dint of our rejection of the International Criminal Court, tolerance for torture, indifference to detainees rights, etc. A primary reason why all that's so distressing is that its undermined the U.S.'s role as a champion for human rights around the globe, setting back both our influence and the struggle for human rights itself. The damage is serious, but its neither complete nor irreversible. Our role in the apprehension and trial of Charles Taylor is a reassuring, though fleeting reminder of the kind of force in the world we can and must again be.